3,600 words spent trying to remember the name of a hotel I stayed at nine years ago

(15-minute read)

In the fall of 2016, which wasn’t that long ago, I went out to Los Angeles for work. A group of colleagues and I had to stay there for three weeks. This was the longest trip I’d ever been on, and the longest stretch that I’d ever stayed at a single hotel. Before we left New York, we speculated that our company might book us in the nice hotel that we’d all heard about. And they did. Soaring across the continent, through a long evening, watching Casablanca for the first time on a tiny seatback screen, I felt royal. Taking off usually fills me with excitement, and so landing is always ten to fifteen percent sadness. But not this time. Because I knew I was going to this particular hotel.

But I don’t remember the name of the hotel anymore. And it’s like a pebble in my shoe in my brain.

Vanity is part of it. Not being able to remember The Name makes me feel that I am getting old and useless and unattractive. In another way, a way that realizes that no one knows nor cares that I ever stayed at this hotel, or whether I can remember anything about it, it just makes me feel emotionally heavy: If I can’t remember the simple facts of what I experienced, what good is experiencing anything?

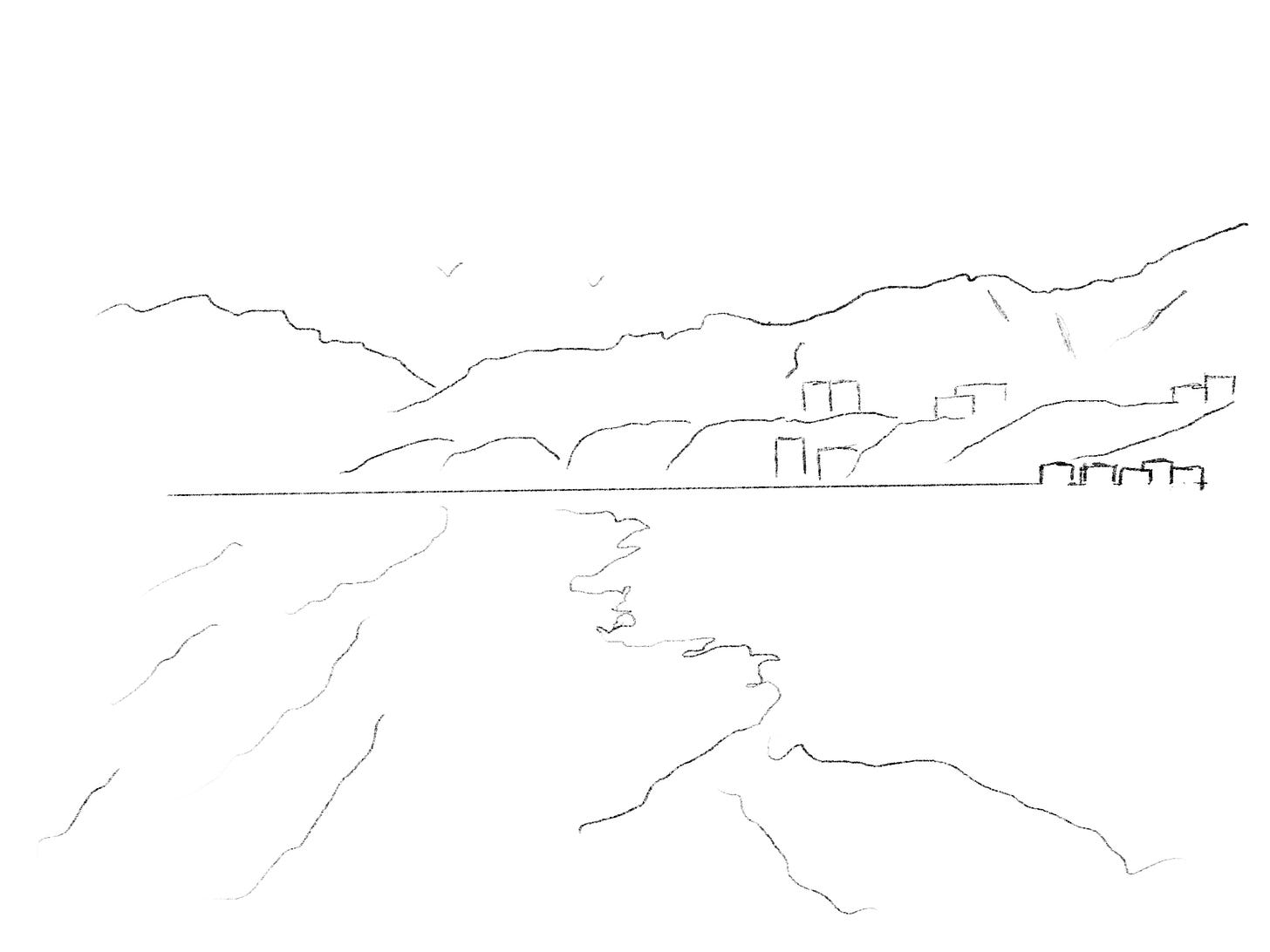

The Hotel was right on the western edge of Santa Monica, California, about two football fields away from where the continental United States ends. Across the street was a long, tidy ocean-side park that you’ve seen so often in TV shows and movies that, like Central Park in New York, you probably just assume you’ve been there at some point. Through the park there’s a long traffic ramp with a sidewalk that will take you down across the Pacific Coast Highway and drop you onto the beach, and across a combed and flattened sand dune was the Pacific, as bottomless and endless as space. The breeze was constant.

I’ve stayed in hotels founded by 19th century railroad barons, and in sleek contemporary hotels so new that they called their rooms “pods” and don’t yet feel ashamed of doing so. This hotel wasn’t either of those. It was a white, concrete T, with another white concrete T on top of it, and so on and so up for 10 to 15 stories with tinted sliding doors and balconies between each story. If it was somewhere scrubbier and more humid, like Myrtle Beach, the building would have been the architectural equivalent of a chest hair beneath an open a polyester shirt.

But as it was, where it was, it was majestic. Your uber pulled into the Nixon-era complex on cobblestones and rounded a massive tree that was the oldest-looking thing I ever saw in California. You could imagine it being watered as a sapling by the urine of passing Conquistadores. Coming from the east coast as I did, the tree looked slightly alien; its trunk was gray, not brown, and its bark was more like skin, layered over itself and peeling in places, revealing patches of soft, damp chartreuse. All around the driveway were bushes with dark fuschia flowers, and their red-purple smell idled in the air by the main entrance, along with the saline humidity and car exhaust. Now and again, years later, I’ll be watching TV and suddenly see the front entrance to The Hotel in a car commercial, with a new Lexus pulling up in the front and an overdressed bellhop opening the passenger side door for an ethnically ambiguous, commercially attractive woman in her late-20s or early 30s.

As I got out of my Uber and unloaded my luggage, I felt like I was simultaneously acting in and watching a commercial for my own life.

When you walked in through the driveway entrance, the doors slid open onto a large, high-ceilinged lobby. To the right and the left there were waiting areas. No matter what your state of mind when you sat down there, it would look like very important people were late for an appointment with you, but that you hardly cared. There were large, dark chairs that were really hard to get up from. In the middle of the lobby there was a table that would take 19 stout men to lift off the floor and on the table was a bronze vase and in the bronze vase were gigantic flowers. The floors and walls were solid old-rose marble.

Across the lobby, past the table, was the restaurant. The far wall of the lobby was sliding glass, and every morning the glass would roll away and the lobby would open onto a courtyard garden with a koi pond, palm plants and a burbling waterfall. Half of the restaurant’s white tableclothed tables were inside and half were outside, though the arrangement seemed to chuckle in a light and indistinct Spanish accent, that “inside” and “outside” were meaningless concepts here.

Every morning before the car picked us up to go wherever we were working that day, I would drift down to the lobby and get breakfast. It made me feel like a much richer person than I am. I’d scan the tables and see a colleague already cutting French Toast and I’d join them without even wondering if it was a faux pas. All the waitresses were older Filipino women, and one of my colleagues was a younger Filipino man. When I sat for breakfast with Romeo he would flirt with them, pay for both our meals - an omelet was something like $27, but everything was being reimbursed by the corporate client, so whether it went on my card or his, money was only a dreamy detail - then check his texts and tell me that the driver was here.

Past the restaurant tables, through the garden courtyard, you could get to The Bungalows. That was the hotel’s outdoor bar and probably what the hotel was best known for. It was an easygoing space, walled in by tall shrubs so you could hear the traffic passing on Ocean Avenue, but all you could see of the world beyond was the pink-orange sky and the occasional silent, floating seagull. Inside the shrubwall there were fancy sheds, some of which served drinks I think, and some pool furniture but no pool. After six o’clock in the evening there was a constant stream of Ubers and people walking in off the sidewalk, to go to The Bungalows, and it stayed loud and multicolored late into the night on weekends. But we only had one drink there, once, while waiting to go to dinner somewhere else.

I remember exactly the name of the hotel across the street. It wasn’t as nice or as famous. There was worn, burgundy carpeting in the lobby and the elevators were glass jars visible on the building’s exterior. It had a bar on or near the roof that someone in our group once wanted to go to, but my memory ends right there in the lobby. I don’t think we made it up. Either it was closed or we changed our minds about going. That hotel was The Huntley. I could never possibly forget that, because The Huntley was also the name of a primitive submarine that sank in Charleston harbor, South Carolina, after a failed attack on a Union blockade ship during the Civil War: The Huntley, yes. In addition, my daughter was just over one year-old at the time and she loved watching Curious George on PBS. Huntley was the name of the dachshund that belonged to the doorman in the building where Curious George and the Man With The Yellow Hat lived. George and Huntley had a number of adventures together. I remember the name of The Huntley so well, with almost sonic clarity, that when I try to remember the name of the hotel where I actually lived for a month, the name that comes instantly to mind is The Huntley. But as surely as it comes I know that it is wrong.

My room in The Hotel was nothing special architecturally or decor-wise. Two queen beds, a bathroom and a flatscreen on a dresser. It’s one of those spatial memories that’s hard to determine where you saw it: in a moment and place that you yourself experienced, or in a picture on a website. Or it would be, if it weren’t for the view. My room was on the seventh or eighth floor, and a sliding door led out onto a balcony that looked south. Looking south, from that height, in that place, you saw what seemed to be everything: The Pacific Ocean most of all, endless, smudged by humidity and blue or sometimes so much darker blue that “blue” doesn’t really describe it, but has to anyway because except at night the water was never quite black.

And the sky - blue, pink, orange and purple at various points - even endlesser than the ocean, and lit up with a string of gently descending, blinking white lights: planes landing at Los Angeles International Airport, which I could also also see, along with buildings that held millions of people; and the Santa Monica Pier with its ferris wheel and roller coaster and solitary fisherman hanging off the end of it; and beaches; and at the edge of my view, the Palos Verdes Hills, where a few 18th century Spanish shepherds grazed their sheep, and which now seemed to be the only things between me and the edge of the universe.

The balcony was hardly 3 feet-wide so it was hard to spend any real time on it. But it had a little white, plastic patio chair where I sat and called my stepdad and told him everything I could see. The sun sparkling in the water was almost too bright to look directly at.

The room also had a little one of those narrow, perfunctory hotel room desks, the kind designed for people with 12-inch arms. That was where I sat on a Saturday afternoon with my laptop open, and my phone beside it, and called voters in North Carolina. This was late September and early October in the first year of what would become the Trump era, and I was getting nervous. Back then, phonebanking from your laptop was new technology. I hated it just as much as I hated phonebanking from a landline on a folding table in a dingy political committee office in North Jersey. And I hated calling North Carolina specifically because they did not like Hillary there. Except for this one guy. The phone rang. The call clicked through. I threw up the scripted shpiel I’d swallowed and then asked him if he planned to vote for Hillary.

“Yes, yes sir,” he said respectfully, as if I was someone to him.

This was a little surprising, given all the people who hung up on me. But not as surprising as the fact that all these years later I clearly remember those three words and how he said them.

More than that, I have a distinct memory of seeing this guy - which I never did. I only spoke to him, for less than 30-seconds, over the phone. But when I recall this episode, which hardly rises to the level of “episode”, I see him: He’s a stocky white guy who hasn’t shaved in a few days, but doesn’t yet have a beard, and he’s wearing a cammo baseball cap and he’s walking down a hall as he’s listening to me talk at him on the phone. He steps into an elevator, replies that he’s voting for Hillary, and then the elevator doors close and the call ends: Either he hangs up or the signal drops.

How did I get all that? Did I hear something in the background of the call that I’ve since forgotten? The ding of an elevator bell? Or the slow, metallic schwoop of an elevator door closing? And from that, did subconsciously conjure an entire scene that I remembered over a decade after I forgot the auditory clue that started the fantasy? It’s plausible I guess. But if so what sound does a cammo baseball cap make?

More importantly, what was the name of the hotel I was staying at when this all happened?

A few evenings later I was sitting at that same purely decorative desk, trying to send out some work emails when my internet connection blinked out of existence. I restarted my computer. I logged on and off the network. I did all the things and still, no internet. I called the front desk, which kicked me over to the hotel’s corporate IT line, which put me on hold for a bit, and after pinging all the things that could be pinged, told me that the internet’s disappearance was an unfathomable mystery. So I went to bed.

The next morning at breakfast several colleagues told me that the same thing had happened to them. The internet was out all night. The morning after that, one of them had an explanation they’d gotten from the front desk: Hillary Clinton had been staying up in the penthouse suite after a fundraiser in Los Angeles, and the Secret Service had chloroformed the internet for security reasons.

She was long gone by the afternoon I came back into the lobby after going out for a run on the beach. I’d plodded my way on a hot, sandy asphalt path all the way up to where it seemed like I might plausibly reach out and touch the Malibu hills, and then back again, barely. I was a damp. flush mess and when I sorestepped my way back through the hotel lobby it was cool and dark, like the most beautiful cave in the world. I saw CNN playing on a flatscreen by the entrance. The director of the FBI, James Comey, had notified Congress that he was re-starting the investigation into Hillary’s emails. A tiny-eyed Utah Congressman with short, curly black hair, and a permanently upturned nose was braying on screen. I was too sweaty to stand in public and keep watching, so I got in the elevator to go up to my room, but as I went up my stomach went down.

Another memory: A very specific conversation I had in high school, in English class. It was just after the bell had rung and a couple of us were talking with the teacher, Mr. Wojcik - and he asked a question: Is it possible to think, really think, without using words in your head? Without narrating to yourself what you were thinking? I closed my eyes and tried to think of a sunset, specifically a sunset, without thinking of the word “sunset.” I saw the orange ball and the black horizon. I could do it. And doing it felt pure and intense in a way that thinking usually didn’t. But it was harder than it seemed. I couldn’t keep the image fixed for more than a second or two before my inner monologue blurted something out. The other kid in the conversation, Shane Reilly, had the same experience. Mr. Wojcik said it was tricky, but we actually practiced the skill of thinking without words much more often than we realized: Whenever we try to remember the name of a specific person or thing or concept but can’t quite recall it, and we concentrate ever more intensely trying to get that name, then we’re doing it - we’re thinking without words.

There’s something to that. Over the years I’ve tried to remember the name The Hotel many times. And I have used words in my head every time, usually some variation of “motherfucking goddammit what was the name of that hotel?” Right here I’ve used almost 2,800 words. But because I can’t remember its name, The Hotel in Santa Monica is far more pure, urgent, delicate and beautiful a place than it would be if I could remember what it was called. If I knew its name I wouldn’t have to keep walking up and down its halls. So I have to stay here, in The Hotel in my brain, the place that is just beyond my grasp.

And there’s more if you can believe it. I almost can’t. The memory set I have of The Hotel is like that scarf that birthday party magicians pull out their ear: It just keeps coming.

There was the gray cinderblock Crossfit studio a few blocks down one of my colleagues took me to, where a Korean-American guy wearing his hat backwards ran my credit card and then I did so many sit-ups (“so many” being highly relative, it may have been as few as nine) I almost puked.

And then there was watching the Chicago Cubs pull ahead in the World Series at The Hotel’s bar, on a stool next to another guest, a scruffy white guy from Chicago, who was so in awe of what was happening he could barely speak. I didn’t remember that until I began this paragraph. I could go on.

For as many things as I do remember about The Hotel, there are even more things that I know I don’t remember: The faces of anyone who worked there, or what the bathroom in my room looked like. I don’t remember leaving The Hotel for the last time, what exactly I did or what the weather was like that day. I can use probability to guess: I most likely checked out at the front desk in the same way you always do, and I probably got into a car to the airport, and it was probably beautiful and cloudless because that’s how it usually is in Los Angeles. But I can’t say I remember any of it. At least not yet.

You’ve come an awful long way with me here, so I want to be completely honest with you:

I remembered the name of The Hotel. About 1,500 words back.

I had thought that if it ever came to me - and I was doubtful - that it would come in lighting.

Not so.

The Name popped into my head with no context. I wasn’t even thinking about The Hotel at that moment and I didn’t put the two together. It was like remembering the name of someone I’d once met but without being able to visualize their face, or construct a story about when and how I’d met them. The Name weighed almost nothing. So I let it go. Eventually it floated back in and now its edges were sharper and its center was darker. I let it float by again. And it came back again.

So I put The Name together with The Hotel. It wasn’t a bespoke fit, but it made sense. The Name was plainer than I’d imagined it would be, though honestly after a while I’d lost my curiosity about it. I’d been focused on squeezing every last sight, sound and texture from my memory of The Hotel. That was the fun part. After doing that for so long I almost forgot that I had forgotten The Name of The Hotel. I should put that another way: After so long of not having The Name of The Hotel, I found I didn’t need it. Actually, I didn’t want it.

Now that I know what The Hotel is rightly called I’m a little anxious.

I think it’s possible that now that I remember The Name I will start to forget The Hotel. That it will sidle over in my brain to the dry field where I keep hotels that have names I can remember: The Holiday Inn Turf on Wolf Road, the Desmond, Yotel New York, Citizen M, The Downtown Rochester Courtyard by Marriott. These are or were fine establishments. I remember them all. I can remember them anytime I want, and they don’t mean particularly anything.

I don’t know how many of you are still with me this far in. I can’t see why you would be. I hope you took an unmarked exit somewhere a ways back and went to visit hotels that you’ve stayed at, hotels that you may or may not remember the names of.

But if you are still with me, I’d like to ask you for a favor: Please don’t mention the name of The Hotel in the comments. Some of you live in LA. Many others have traveled there. You might have figured out The Name from the first paragraph, and certainly from the bungalows bit. And anyone else could get it with a 10-second google.

But don’t say it. Don’t type it. You’ll notice that I haven’t. I haven’t even google-checked the name that I think is The Name. I don’t want to do anything that will strengthen my synapses or solidify the association. It’s probable that I have forgotten, remembered and re-forgotten The Name of The Hotel many times in the nine years since I left. But I’m not sure. If I have, I’ve forgotten the specific process and instances of forgetting and remembering.

What I am sure of though is that I will forget again. The Name will check out of my mind in the middle of the night. It will leave its keycard on the front desk and walk out.

And honestly, I can’t wait.

“You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.”

My relatives in Hawaii would like to thank you for noting it as the end of the continental US. If they got a dime every time some "god damn cockamamie shit lolo tourist" (apparently my dad's most trotted out phrase) said "Back in the US," they'd have been able to buy Parker Ranch three times over.

Also: I had to google it but the search confirmed I'd guessed The Hotel. My honorary aunt lives in Santa Monica, so I had an unfair advantage.